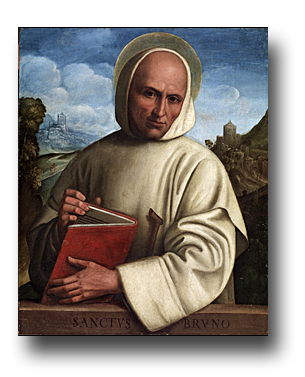

- Saint Bruno Père des Chartreux Transcription

du texte

du DVD (acheter)

du DVD (acheter)

- Article

from the Catholic encyclopedia

- Feast

of Saint Bruno 2003, The Poor of Christ

- Feast

of

Saint Bruno 2004, I am making all things new

- Our Father Saint Bruno, a Sermon of the

Reverend Father General of the Carthusian Order at the

1983 General Chapter

- Biography

of

Saint Bruno

- Prayers

to Saint Bruno

- Saint

Bruno's Profession of Faith

- Le 19 juillet 2014, nous fêtons le 500e anniversaire

de la canonisation de Saint Bruno, fondateur du Monastère de

la Grande Chartreuse et de la congrégation des Chartreux. Le

prieur de la Grande Chartreuse, Dom François-Marie,

a accordé un entretien exclusif à RCF Isère. Aux micros

d’Annie Francou et Stéphane Debusschère, il raconte

l’histoire de Bruno né à Cologne et qui, un jour de 1084

vient rencontrer l’évêque de Grenoble, Saint Hugues. Ce

dernier accompagnera Bruno et ses compagnons dans le désert

vert de Chartreuse pour installer une première communauté de

religieux ermites. Cet entretien est l’occasion d’aborder la

spiritualité des Chartreux, leur place dans le monde et la

raison du rayonnement de leur engagement fait de prière, de

solitude et de silence. Les entretiens croisés de l’évêque

de Grenoble et du Prieur abordent la question de l’actualité

des relations entre le diocèse et le monastère, comme si

l’histoire de Bruno et de Hugues poursuivait son chemin

aujourd’hui.

- Biography

-

from the Charterhouse of The Transfiguration website

- Saint

Bruno Cross

| Short Biography of St Bruno |

« O Bonitas! » |

| Bruno was born in Cologne

around 1030. He was still a youth when he was sent to

Rheims, in France, to study at one of the most reputed

universities in Europe. After completion of his studies, he

started teaching at that university. In 1056, Archbishop

Gervais chose him to be the Rector of the "schools" of

Rheims; he held the office of Rector of studies for 20

years. Towards the end of 1076, Bruno chose exile because of

the conflict between Manasses of Gournay, the archbishop of

Rheims, and several important institutes of the city,

including the Benedictine monastery of Saint Remi. On

December 27, 1080, Gregory VII had to resolve to ask the

clergy of Rheims to drive the corrupt archbishop away and to

elect a new one. Bruno was chosen for this post of high

responsibility and power, one of the highest ecclesiastical

positions in the kingdom of France. But he had other plans.

He had decided to follow Christ to the desert. It is only

around the Feast of St John-Baptist, approximately on June

24, that he and six companions reached the far end of the

desert of Chartreuse, under the guidance of Hugh, the young

bishop of Grenoble. For six years, Bruno was able to enjoy

the life he had chosen with his brothers. In the first

months of 1090, Urban II, a former student of his, summoned

him to Rome to help him in the service of the Church, but

just a few months later, Bruno obtained the Pope's

permission to return to eremitic life, provided that he

would establish his hermitage in southern Italy, then under

the rule of the Norman princes. Bruno chose a vast desert in

the diocese of Squillace : Santa Maria della Torre. This is

where he died, on October 6. 1101. From there he wrote two

letters full of tender love which have been inspiring

Carthusians for nine centuries. Bruno was beatified by Pope

Leo X in 1514. |

|

Long Biography of Bruno by Fr André Ravier, s.j.

The twelve chapter titles below are links to the

main chapters of André Ravier's (1905-1999) biography of Saint

Bruno : André Ravier, s.j., Saint Bruno The

Carthusian, written in 1981 and translated by Bruno

Becker, O.S.B., Ignatius Press, San Fancisco, 1995. These

extensive excerpts (almost the complete book, slightly edited for

web purposes and updated, but without the footnotes and index)

from the pen of a writer who wrote so many books on Carthusian

history and spirituality are included here for their inspirational

value and for a fuller understanding of Bruno's soul through his

historical circumstances. It is an important read for an admirer

of Bruno and for any serious student of the Carthusian Charism.

The book is out of print; it is reproduced here with the kind

permission of Ignatius Press.

Prologue

On a June morning in 1084, about the time of the

feast of Saint John the Baptist, a small, serious-looking group of

poorly clothed travelers left the Bishop's house in Grenoble,(1)

led by young Bishop Hugh. They headed north and took the road to

Sappey. After passing the last houses of the town they entered the

great forest, cleared the Palaquit Pass, and reached the Porte

Pass at an altitude of 4,000 feet. From the pass they descended to

the village of Saint-Pierrede-Chartreuse over a path that today's

road follows closely. But, shortly before they reached

Saint-Pierre, they turned left into the Valley of Guiers-Mort.

This very narrow valley grew narrower little by little until it

was enclosed between two steep cliffs. Only the stream and the

path found an exit to the west.

The "Gateway", as this valley was called, was

the sole entry from the south. A little beyond that, to the right,

an oblong valley called the Wilderness of Chartreuse extended

north-northeast about three miles. Its lowest point was 2,350 feet

above sea level, and the highest was 3,450 feet. It was nearly

enclosed on all sides by towering mountains which, at the Grand

Som, reached an altitude of 6,000 feet. Except for the gateway of

the valley, there was only one other way to enter. That was by La

Ruchère Pass (4,250 feet) toward the northwest, though the village

of La Ruchère itself was accessible only by the dangerous route of

the Frou, over two poor paths that were long, difficult, and very

risky: one coming from Saint-Laurent of the Wilderness in the west

(today called Saint-Laurent-du-Pont), the other from

Saint-Pierre-d'Entremont in the north. The latter went through the

forest of Eparres, the home of wild animals, and up over the

Bovinant Pass to an altitude of 5,000 feet. In this wilderness the

travelers boldly summoned up their strength at the gateway of the

valley and, since they were looking for the wildest place in this

wild place, they climbed to the farthest point toward the north,

where the wilderness terminated in a gorge that was enclosed by

mountains so high that during most of the year the sun scarcely

penetrated it. Amid the fallen rocks the strangely shaped trees

still reached for the sky, so that at least their tops might gain

the open air, light, and warmth. Then the little band stopped.

They had arrived. Bishop Hugh told his companions they should

build their huts here and make their dream of a hermitage a

reality. Taking leave of his companions, he went back down to

Grenoble with his personal escort.

Seven men stayed in the Wilderness: Master

Bruno, the former chancellor and canon of the Church of Rheims;

Master Landuino from Lucca in Tuscany, a renowned theologian;

Stephen of Bourg and Stephen of Dié, both canons of Saint-Ruf;

Hugh, "whom they called the chaplain because he was the only one

of them who functioned as a priest"(2); and two "laymen", Andrew

and Guérin, who were lay brothers. These seven had decided to lead

an eremitical life in common, and for some time they had been

looking for a suitable place to carry out their project. Prompted

by the Spirit and knowing surely how well forests in the Dauphiné

were suitable for solitude, Bruno came to Hugh, bishop of

Grenoble, to ask for shelter and advice. And Hugh, inspired by a

wonderful dream, chose the Wilderness of Chartreuse for Bruno and

his companions.

Human wisdom would say the selection was

foolish. The harsh climate with heavy snowfalls; the poor soil

that required so much labor to provide even meager nourishment for

its inhabitants; the ruggedness of the terrain that made

cultivation difficult in the forest; the inaccessibility of the

place during a considerable part of the year, so that there was no

hope of obtaining help quickly should there be an emergency or

fire or illness. Everything was against establishing any sort of

permanent dwelling for human beings in the Wilderness of

Chartreuse, and especially in this northern end of it. Several

times events demonstrated that these fears were well founded. On

Saturday, January 30, 1132, an enormous avalanche fell upon all of

the cells except one and killed six hermits and one novice. They

were compelled to go back a mile and a half toward the south from

the end of the Wilderness, where the Grande Chartreuse is located

now.

Bruno was more than fifty years old. Several of

his companions, notably Landuino, were no longer young. What

secret desire impelled them to brave this solitude, whose severity

Guigo, in his Customs (Consuetudines or Custumal) alludes to

twice? What discovery, what pearl of great price could make them

live "for a long time amid so much snow and such dreadful

cold"?(3)

The mystery of vocation, by which God calls

certain people to a purely contemplative life and all-embracing

love; the mystery of hidden lives of self-effacement (as it is

commonly regarded) with Christ who effaced himself; the mystery of

the prayer of Christ in the wilderness during the nights of his

public life and at Gethsemane, the prayer of Christ that continues

in certain privileged souls at every period in the history of the

Church; the mystery of being solitary while remaining present to

the world, of silence and the light of the Gospel, simplicity, and

the glory of God: this is the mystery we will try to discover in

the soul of Bruno.

Saint Bruno's Childhood

The six companions called him "Master Bruno". It

was not only because he was older or because he had once been

their teacher at Rheims, but because they regarded him highly, and

respected him. Over them he had a moral power, which radiated

constantly from his whole character and could not be explained

simply by their past. If they had come to the Wilderness of

Chartreuse, if they had joined this bold project, it was because

he led them, because they were drawn to follow him on account of

the way he had clarified God's call for them and inspired

confidence in them. The goodness, the balance, the desire to seek

God in absolute and total love that they saw in him captivated.

And they were still captivated. He was the one who had formulated

the project and carried it forward to its conclusion.

So, who was this man who had such an effect on

his companions? Practically nothing is known of his beginnings.

Only three facts are certain. He was born at Cologne — so he was a

German — and his parents were not without nobility, or at least

not without some good reputation in the city. Toward the middle of

the sixteenth century, it was said that he belonged to the

Hartenfaust family, even that he was descended from the "gens

Æmilia", but there seems to be no foundation for that claim. It

was based merely on an oral tradition at Cologne. In a document of

August 2, 1099, whose authenticity unfortunately is contested,

Bruno is said to have refused an important donation from the Count

of Sicily and Calabria. "He refused," runs the text, "telling me

he had left his father's house and mine, where he had held the

first place, for the purpose of being able to serve God with a

soul completely unencumbered by the goods of earth." The lack of

authenticity in false documents is often camouflaged by some

details that are true. Is that the case here?

What is the date of Bruno's birth? We do not know

that, but, calculating from the date of his death — which was

October 6, 1101 — and from the events of his life, there is no

great risk of error placing his birth between 1024 and 1031. The

year 1030 best agrees with the events that mark his life.

Bruno lived the first years of his childhood in

Cologne. No document dating from that period has come down to us.

Cologne! Ancient Colonia Claudia Ara

Agrippinensis, which the Romans had founded between the Rhine and

the Meuse, had been independent of county organization since the

time of Otto the Great, who had placed his own brother Bruno

(953–65) upon the archiepiscopal see. He had transferred the

administration of justice to him and, to him and to the

archbishops who would succeed him, the rights of a count. When

Bruno, the future founder of the Carthusian, was born, the name of

the archbishop was Peregrinatus. He was the one who crowned Henry

III at Aachen in 1028 and thereby acquired for the archbishops of

Cologne the right of crowning the emperor. When Bruno lived, there

was a historical connection between Cologne and Rheims, which

might be of some interest here. He found himself tragically

involved in the grave disturbance Archbishop Manassès had stirred

up at Rheims by his simoniacal election and by his conduct, while

at about the same time the Church of Cologne was experiencing a

similar situation. Archbishop Hidulf (1076–78) sided with Emperor

Henry IV of Germany against Pope Gregory VII in the struggle of

Investitures. Hidulf's successors, Sigewin (1078–89) and Herimann

III (1089–99), continued his policy. At least during the period

from 1072 to 1082 Bruno surely maintained some communication with

his people at Cologne. He would have been aware of what was going

on in his hometown. If this conjecture is correct, the great trial

of conscience, which prompted him to leave Rheims and join the

resistance to Archbishop Manassès, would have come from the two

churches that were the most dear to him.

But to return to Bruno's childhood. Archbishop

Bruno I, through his talent for organizing, made Cologne not only

the first city of Germany but also one of importance in the world.

This civic-minded man was also a spiritual man: he promoted the

eremitical and the monastic life, built churches, and founded

cathedral chapters, so that the city was called "holy Cologne" or

"the Rome of Germany". When Bruno, the future Carthusian, was a

child, Cologne was still experiencing the intense spiritual life

that Archbishop Bruno I had given it. It had no fewer than nine

collegiate churches, four abbeys, and nineteen parish churches. At

this time, the only schools where children could be introduced to

classical studies were in monasteries and churches. To which of

those schools was Bruno entrusted? That will never be known with

certainty. But, since he was named a canon of the cathedral church

of Saint Cunibert, we can with reason deduce that he had had a

particular relationship with that church. Was he sent to that

school because his family belonged to that parish?

One fact seems beyond any doubt. Even in his

first studies Bruno gave evidence of striking intellectual gifts,

because while still young (tenerum alumnum, as the canons of

Rheims will later say) he was sent from Cologne to the famous

cathedral school of Rheims. That is where he would live from then

on. While he stayed at Paris, Tours, or Chartres, the story was

the same. It was Rheims that especially left its mark on him, with

the result that, though he was of German origin, people later

called him Gallicus, the Frenchman.

The schools of Rheims, and especially the

cathedral school that Bruno attended, had been renowned for

several centuries. Gerbert, who was one day to become Pope

Sylvester II, was their rector from 970 to about 990, and they had

been enlightened by his talent. In the eleventh century Archbishop

Guy of Chastillon gave a new impetus to learning. When Bruno came

there to study, the schools of Rheims had attained some

prominence, with students coming from Germany, from Italy — in

fact, from all over Europe. Among all these young people it was

the personality of Bruno that attracted the attention of the

teachers.

At that time learning was encyclopedic, and the

humanities were said to serve as a preparation for theology. After

studying grammar, rhetoric, and logic (the trivium), the student

applied himself to arithmetic, music, geometry, and astronomy (the

quadrivium). Only after that came theology, like the crown of all

human learning. But if — as it often happened, and a notable

example was Gerbert, who excelled in mathematics as well as

theology — if one teacher were to go through the whole cycle of

studies with the same students, he was allowed a certain freedom

in the distribution of the studies. The method of teaching was the

lectio — a lecture with a commentary from ancient writers who were

authorities on the subject. Theology followed the same method,

consisting principally of reading the Bible along with the

master's commentary, which was based on the Fathers of the Church.

Bruno's studies went like that. Hérimann or

Herman was then director of studies (l'écolâtre) at Rheims. He did

not have the same breadth of talent as Gerbert, but he was known

to be a theologian of great merit.

If we can believe the Eulogies (Titres Funèbres),

it was in philosophy and theology that Bruno excelled. But extant

letters written by him provide evidence that he was not ignorant

of rhetoric. The Chronicle Magister, too, asserts that "Bruno . .

. was firmly grounded in human letters as well as in divine

learning." If we can believe a tradition that seems trustworthy,

it is from this period of studies that he wrote a short elegy

entitled "On Scorning the World", which would for the first time

reveal his gift for reflection. This is written in elegant,

balanced, and metrical couplets, in the manner of exercises in

poetry that are practiced during the study of the humanities. But

just now the thought is of more interest than the form. This

elegy, for example:

The Lord created all mortals in the light, offering the

supreme joys of heaven according to their merits.

Blessed is the one who without straying directs his soul

toward those heights and is vigilant to preserve himself from

all evil.

Blessed again is the one who repents after sinning and often

weeps because of his fault.

Alas! People live as though death did not follow life, as if

hell were only an unfounded fable, though burning embrace.

Mortals, have a care that you live, all of you, in such a way

that you do not have to fear the lake of hell.

Bruno was about twenty years old and still a

student of the cathedral school when an event occurred that had to

make a profound spiritual impression upon him: Pope Leo IX came to

Rheims and held a Council (Leo IX visited Cologne in the same

year), arriving at Rheims on September 30, 1049. On October 1 he

effected the transfer of the relics of Saint Remi, which Hincmar

had caused to be taken to Epernay during the Norman invasions. Now

they were returned to the famous abbey. On October 2 Leo IX

consecrated the new church of the abbey of Saint Remi. Saint Remi!

Bruno's devotion for him is revealed in a letter to Raoul le Verd.

When Bruno wrote this letter, he was in Calabria, nearing the end

of his life. He had left France and the Chartreuse some ten years

earlier. The letter to his friend concludes with these words:

"Please send me The Life of Saint Remi, because it is impossible

to find a copy where we are."

On October 3, as soon as the festivities for

Saint Remi were concluded, Leo IX opened the Council. Numerous

archbishops, bishops, and abbots participated in it. They were

particularly concerned with simony, which was then threatening the

Church and urgently needed to be eliminated. Several bishops who

were accused of having bought their bishoprics were summoned. The

Pope and the Council deposed and excommunicated them. Then

disciplinary decisions were made to put an end to that evil.

Because he was participating in the ceremonies, Bruno was aware of

the measures and decisions that the Council took, the presence of

the Pope giving them authority and extraordinary solemnity.

So, at the beginning of his productive life,

Bruno was confronted with the great problems of the Church.

Profoundly religious and honest, formed by Holy Scripture and the

great principles of the Faith, he was drawn to reflect on the

situation of the Church, the needed reforms, and the direction his

life had to take to reach its fullest worth and integrity. For the

moment it seemed the Lord was inclining him to religious studies

here at Rheims. There was nothing to indicate he was dreaming of a

hermitage at that time. On the contrary, while he was pursuing

sacred studies, he was deeply involved in the life of the diocese.

The events of the next thirty years would plunge him into an

emotional crisis in which what he had seen Leo IX and the Council

accomplish would enlighten and direct the choices he would make.

Master Bruno

After completing his studies did Bruno spend a

short time in Paris? Did he return to Cologne for a while? Did he

receive sacred orders? Did he preach? and if so, where? So many

uncertainties, and no reliable documents. There is only this

indication in one of the Eulogies: "He gave many sermons

throughout the area" (Multos faciebat sermones per regiones). It

would not be prudent to draw any conclusions from that, though,

because any cleric who had finished his studies with a degree from

the school at Rheims could be called to preach to the people.

It would be enlightening for a historian to know

when and in what circumstances Bruno was promoted to be a canon of

the church of Saint Cunibert of Cologne. Unfortunately, we know

only the bare fact, and it is Manassès, the simoniacal Archbishop

of Rheims, who gives it to us in the Apology that he addressed to

Hugh of Dié and the Council of Lyons in February 1080: "This Bruno

does not belong to my clergy. He was neither born nor baptized in

my diocese. He is a canon of Saint Cunibert at Cologne in the land

of the Teutons." We can only guess about the date and

circumstances of his promotion. The first hypothesis is to connect

it with the reorganization of the collegiate church of Saint

Cunibert by Archbishop Herimann II of Cologne. This cathedral

church had twenty-four canons. Did Herimann wish to honor Bruno's

family and to create a personal link with the church of Cologne

for Bruno himself, whose gifts were already evident? According to

this conjecture Bruno would have become a canon while still a

young man. Or did he have to wait until the excellence of his

teaching made him famous? Cologne would have wanted to contribute

to the honor being given to one of its sons. That seems most

likely. But another theory has often been put forward: that in

1077 or a little later, at the time of the conflict with Manassès,

Bruno returned to Cologne. This does not seem likely. In addition

to the fact that the documents seem to indicate he and the other

canons who had opposed the simoniacal Archbishop were staying at

Count Ebal of Roucy's, how would he find shelter in Cologne, where

the situation was even worse than at Rheims? In March of 1076,

Emperor Henry IV had imposed upon Cologne an intruder named

Hidulf, one whom the clergy as well as the people who were

faithful to Gregory VII opposed to no avail. Given the present

state of research, only this is certain: Bruno was a canon of

Saint Cunibert.

If Bruno was born around 1030 (the year suggested

above), there is still a problem. What did he do after finishing

his studies until he was promoted to the post of director of

studies (l'écolâtre) for the schools of Rheims? What was his life

like? How did he use his time? The answer seems certain. In any

city, and most of all at Rheims, such a responsible assignment as

summus didascalus must have been entrusted to a professor who had

demonstrated his abilities. If Bruno spent time at Paris or

Cologne, his stays there were brief.

What is more, even before being named director of

studies (or at least about the same time), Bruno was called to

another dignity. He was promoted to be a canon of the cathedral of

Rheims. It was no trifling honor to belong to that illustrious

Chapter. "Bruno, a canon of the Church of Rheims, which was second

to none in France" (Bruno, Ecclesiæ Remensis guæ nulli inter

Gallicanas secunda est, canonicus), says the Chronicle Magister.

Bruno did not claim this honor for himself.

Rheims was then a metropolitan see. Its Chapter, comprised of

seventy two canons, was renowned and powerful. It was directed by

the Rule that had been designed for the canons in 816 by the

Council of Aachen at the suggestion of Emperor Louis the Pious. It

was a moderate rule, midway between the regular life of monks and

the freedom of clerics. Canons living under the Rule of Aachen

remained secular, keeping their own possessions, having their own

house, receiving income. Laws of fasting were precise but not

burdensome. Some life in common was required, but it was neither

absolute nor strict. In some Chapters this moderation could turn

into mediocrity, but this does not seem to have happened at

Rheims. Around 980 the Chapter of Rheims was singled out as an

example of perfection "in chastity, learning, discipline, in

correcting faults, and in performing good works" (in castitate,

scientia, disciplina, in correptione et exhibitione bonorum

operum). At the time of Bruno it deserved that praise. When

Archbishop Gervais introduced Canons Regular in the two collegiate

churches of his diocese (Saint Timothy in 1064, Saint Denys in

1067), they lived a stricter observance, especially as regards the

common life and poverty. The Chapter of the cathedral did not

adopt that reform. So, Bruno was a secular canon, never a Canon

Regular.

In the course of the centuries the archbishops of

Rheims and other benefactors had richly endowed the Chapter of

their cathedral. Saint Rémi himself (died about 533) had first

given the example — he bequeathed to the clergy of his cathedral

(the office of canons did not exist then) considerable property,

entire villages, churches, as well as estates with peasants

attached to them. He meant to foster some common life among his

clergy. Other archbishops followed Saint Remi's example. Although

the cathedral Chapter possessed many properties, some of them were

in distant places, even south of the Loire and as far as Thuringia

in Germany. Each bishop committed himself after his installation

to respect the Chapter's patrimony. Every year the income from the

properties was divided among the canons. So Bruno, like the other

members of the Chapter, must have received his share of the

wealth. This income augmented his personal fortune, which, it

seems, was not negligible. Two of the Eulogies from the cathedral

of Rheims (52 and 53) relate that, at the time of his departure

from Rheims, he had an abundance of resources and was divitiis

potens.

If we can judge from what we know of the life of

the canons of Rheims at the time, this is how Bruno, a canon of

Rheims, lived. He lived outside the cathedral cloister, in a house

that was his personal property; he received income that allowed

him to have a comfortable and easy life; he had servants and could

easily receive his friends, since the canons were not required to

take all their meals at the common table. Their principal

obligation was to participate regularly in the cathedral canons'

Office, and we can hardly believe that Bruno would fail to perform

this duty faithfully. Did he visit the monks of neighboring

abbeys? Saint-Thierry was only a few kilometers from the city, and

Saint Remi was just at the gate. He certainly was acquainted with

them and their way of life as his own plan for monastic life

matured. When he left Rheims for Sèche-Fontaine he had great

admiration and friendship for the black monks of Saint Benedict.

He knew, though, that the Lord was not calling him to their way of

life.

Outside the time for the canonical Hours, each

member of the Chapter was free to organize his life as he pleased.

But, if Bruno had been inclined to lengthy contemplation and to a

home of solitude at that time, he would not have been able to

accomplish the tasks the Archbishop entrusted to him. It was 1056,

and he was director of studies for the schools of Rheims.

It would be useful to know the exact date when

Herimann resigned his office as director of studies in Rheims,

because Bruno succeeded him at once. That resignation apparently

took place shortly after Gervais of Château-du-Loir was elevated

to the See of Rheims in October of 1055, which, without much

danger of error, can be placed at the end of 1055 or the beginning

of 1056. Bruno's promotion to the dignity of director of studies

would then be during the year 1056.

It was a great honor for Bruno to be selected.

Calling one so young to occupy a position so sensitive indicated

that Herimann had discovered his exceptional talent for teaching,

communication, and even administration. Bruno was only twenty-six

or twenty-eight years old. Herimann would not have so resolutely

settled upon a man of that age had he not been certain that, in

proposing the nomination to Arch-bishop Gervais, he had the

implicit consent of the professors and even of the students of the

schools of Rheims. Besides, he, better than anyone else, knew the

renown of these schools throughout the whole Christian world.

Rheims was then one of the most celebrated of the

intellectual centers of Europe, and he was obliged to maintain its

high reputation by the judicious recruitment of its teachers.

Bruno had to have already succeeded in the secondary positions

that had been entrusted to him before he was placed, regardless of

his age, over all the schools of Rheims with the rank of summus

didascalus.

The choice of Archbishop Gervais was a good one.

For about twenty years Bruno had excelled among the teachers of

Rheims to the point that one day he was invested by the legate of

Pope Gregory VII, Hugh of Dié, with the distinguished title of

"teacher of the Church of Rheims" (Remensis Ecclesiæ magistrum).

His pupils gathered in the cathedral cloister, where the master

used to teach. Several of them rose to become dignitaries in the

Church. One was Eudes of Châtillon, who, like Bruno, was a canon

of Rheims and then entered Cluny, became prior, was later created

cardinal-archbishop of Ostia, and finally was chosen pope under

the name of Urban II. There were also Rayner, who was to become

bishop of Lucca; Robert, bishop of Langres; Lambert, abbot of

Pouthières; Maynard, prior of Corméry; and Peter, abbot of the

Canons Regular of Saint Jean-des-Vignes. Later, in the Eulogies,

all of these figures acknowledged that the best part of their

formation was due to Bruno. Here are some of their testimonials:

I, Rayner, one of the venerable Bruno's old pupils, wish to

offer my prayers to Almighty God that he will give the crown

to this faithful man whom he endowed with such grace and

piety. I shall preserve his memory in a special way because of

my debt to him and my affection for him.

From the beginning of my religious vocation I, Lambert,

abbot of Pouthières, was a pupil of Bruno, that remarkable

teacher in the science of learning. I will never forget my

good father, to whom I owe my formation.

Peter, abbot of Saint Jean-des-Vignes at

Soissons, said:

Learning of the death of Bruno, your holy father, the master

from whose lips I was taught the holy doctrine, I was

saddened, but I also rejoice because he has found rest and now

he lives with God, insofar as I can judge from the purity and

perfection of his life, which I knew very well.

The testimonial of Maynard, prior of Cormery, is

still more moving in that he was preparing to leave for Calabria

when he learned of Bruno's death. He wanted to see Bruno and "open

his soul to him". His desire reveals the depth of Bruno's

influence ever since those days in Rheims:

In the year of the Incarnation of our Lord 1102, on the

calends of November, I received the scroll, and in it I read

that the soul—blessed, I hope—of my dear teacher Bruno had

finished his life of a pilgrim on this earth and entered the

kingdom of heaven on the wings of his virtues, still

persevering in true charity. Certainly I rejoice over the

glorious end of such a man. But, since I was planning to come

to him in the near future so that I might see him and listen

to him, to confide the whole state of my soul to him, and

consecrate myself to the Holy Trinity under his direction

along with you, I am also perplexed about what to say upon

receiving the news of his unexpected death and I have not been

able to restrain my tears. I, Maynard, unworthy prior of

numerous monks in this monastery of Corméry, came from the

city of Rheims. I followed Master Bruno's courses for several

years, and, with the grace of God, I profited from them very

much. I thank Master Bruno for my formation, and, because I

cannot give him my testimonial in this life, I have now

decided the least I can do is give it in behalf of his soul.

This is why, along with all who loved him in Christ, I shall

cherish his memory as long as I have breath.

To these wonderful testimonials of memory and

loyalty, some actions and courtesies of his former students should

be added as well, because without any spoken or written word they

revealed the profound spiritual influence of Master Bruno. One of

these is his nomination to the See of Rheims after the simoniac

Archbishop Manassès was deposed and then the call to Rome that

Bruno received from Pope Urban II. These important events will be

related in their proper place.

Here are some testimonials, selected from the

Eulogies, given by people who knew Bruno: "He surpassed his

teachers and was their master." "Incomparable in philosophy, a

light in every branch of learning". "This teacher had strength of

heart and speech, so that he surpassed all other masters; all

wisdom was found in him; I know what I am saying and all of France

with me." "An understanding master, a light and guide on the way

that leads to the heights of wisdom". "His instruction gave light

to the world." "The honor and the glory of our time". Even taking

into account the literary exaggerations that were customary in

such testimonials, Bruno is presented as a man who undeniably put

his mark upon Christianity during his time. The Eulogies stress

the value of his doctrine, calling him "teacher of teachers",

"source of doctrine", "profound source of philosophy"^ of the

radiance of his spiritual thought, of his "wisdom", "a pearl of

wisdom", "an example for good people", "model of true justice,

learning, and philosophy"; and of his knowledge of Holy Scripture,

especially the Psalter, calling him "learned in the Psalms and

excellent philosopher"; "he had knowledge of the Psalter and, as

doctor, he taught many students"; "once the first teacher for the

schools of the Church in Rheims, well versed in the Psalter and

other branches of learning, he was long a pillar for the whole

city."

In addition to three primary and certainly

genuine texts — namely, letter to Raoul le Verd, letter to the

Community of Chartreuse, and the Profession of Faith (of which we

shall speak below), there are two works that have come to us

bearing Bruno's name: Commentary on the Epistles of St. Paul and

Commentary on the Psalms. If they too are authentic, as they seem

to be, they probably belong to the period of Bruno's life when he

was teaching. Both of them, especially the Commentary on the

Psalms, might have been only notes from a course he gave as

professor of theology. Is it too much to suggest that — even if he

did not keep these notes and carry them with him when he left

Rheims — he at least remembered what he taught by living it in

Chartreuse as well as later in Calabria and no doubt never stopped

improving his ideas and perfecting them for his own use and the

use of his brothers, the hermits?

Is that only a theory? We are certain that, from

the time he was a teacher at Rheims, in the eyes of his students

Bruno excelled in the knowledge of sacred writings and especially

the Psalter. We are no less certain that, both in Chartreuse and

in Calabria, he rejoiced in the fact that his companions were

"learned", and he directed his hermits to study the Bible. Toward

the end of his life he wrote these admirable words to the brothers

at Chartreuse: "I rejoice that, although you do not know how to

read, the finger of the all-powerful God engraves love on your

heart, and knowledge of his holy law, as well." By their

obedience, humility, patience, "chaste love of the Lord", and

"genuine charity", they had the wisdom to receive "the sweet and

life-giving fruit of the divine Scriptures". Nothing could convey

better the extent to which Bruno drew his spirituality and the

sanctification of his soul from his understanding of Scripture. No

doubt this knowledge was more closely directed toward

contemplation in Chartreuse and in Calabria, but could that not be

a continuation, a prolongation, and a deepening of his teaching at

Rheims?

This conclusion would resolve some of the

difficulties that, after eight centuries of agreement, one or

another critic has believed it necessary to raise about the

genuineness of the two Commentaries. To bring up just one example:

it is necessary to take into account the fact that Bruno had

meditated, pondered the contents of these two texts over some

fifty years, and here and there in his teaching he could have

inserted an allusion with a very clear date like the one to Saint

Nicholas in the Commentary on the Psalter, and that would not be

the date of the entire Commentary. Dom Anselm Stoelen had

undertaken a critical study of the two Commentaries, but

unfortunately his death interrupted the work, and no one, as far

as we know, has so far (1981) continued it. At worst—that is to

say, even if an inquiry came to a conclusion against the

genuineness of the twoCommentaries—the portrait of the soul as

sketched above would not be much affected. Bruno would still be,

in the words of one of the Eulogies: "a remarkable commentator on

the Psalter, and a scholar" (In Psalterio et coeteris scientiis

luculentissimus).

The Commentary on the Psalms is of doubtful

interest for the modern reader, and it has in fact been

questioned. In the eighteenth century the learned Maurist Dom

Rivet said in his Literary History of France: "Whoever makes the

effort to read this commentary with a modicum of attention will

agree that it would be very difficult to find another of this

genre that would be more substantial, more illuminating, more

concise, and more clear." But in The Sources of Carthusian Life he

is more reserved: "The Commentary ... on the Psalms is very dry.

Its aridity makes it difficult to read. Besides, it is full of

interpretations that are not palatable to our modern taste."

Perhaps it is wise to take a position midway between that praise

and that reserve. It is true that no contemporary reader should

look in the Commentary on the Psalms for literary pleasure or even

an aid for devotion. But to one who has the determination to

overlook this dryness, Bruno's Commentary will stimulate

contemplation and love for God. Here are some examples of that:

"Happy are they who observe his decrees, who seek him with

all their heart" (Beati qui scrutantur testimonia ejus: in

toto corde exquirunt eum). The ones who seek God by giving

themselves with all their heart to contemplation are those

who, having left all care for the things of this world behind

them, aspire to God alone through contemplation, who seek him

and with all their heart desire only him, who in love delve

into the most intimate secrets of his divinity.

"And I will bless your name forever and ever" (Et benedicam

nomini tuo in sæculum et in sæculum sæculi). I shall praise

you in contemplating your name, which is "Lord"; I shall bless

you with a blessing that will remain through the centuries;

that is to say, I shall praise you by the praise of the

contemplative life, which endures in this century and in the

century to come, according to the word of the Gospel: "Mary

has chosen the better part, and it shall not be taken away

from her." The active life, in contrast, endures only in this

world.

"In my thoughts, a fire blazed forth" (In meditatione mea

exardescet ignis). In my meditation, the love that I already

had has begun, like a burning flame, to grow more and more.

There is no lack of solemn commentaries like

these, which praise the contemplative life and its profound joy.

Here are some more:

Exult in joy, you just, and to achieve it sing to God: that

is, praise him in contemplation. Dedicate yourselves to the

contemplative life, which consists in devoting yourselves to

prayer and meditation on the divine mysteries, leaving behind

all that belongs to earth.

"Shout joyfully to God" (Jubilate Deo). Praise God with inner

spiritual joy, a joy that cannot be explained in speech or in

writing: that is, praise him with an intense devotion.

Though some of the writings may date from his

time at Chartreuse and at Calabria, Bruno's attachment to the

Psalter goes back to Rheims, where, among his students, he had the

reputation of a specialist on the Psalms. Bruno's predilection for

the Psalter—if one may believe the prologue to the

Commentary—rests on the fact that the Psalter is the book of

divine praise par excellence. "The entire Psalter speaks about

things above: that is to say, about the praises of God. The book

has many things to say, . . . but the praises of God are

everywhere.... It is with good reason that the Hebrews called this

the book of hymns, that is, the book of the praises of God." For

Bruno, who had a special gift for praising God, the praise of God

is Christ himself: the life, death, and Resurrection of Christ:

The title of Psalm 54, "For the choirmaster; with stringed

instruments; a Maskil of David" (In finem, in carminibus,

intellectus ipsi David), can be explained this way: This Psalm

can be applied to David himself, that is, to Christ

persevering in carminibus, that is, in praise. Christ praises

God by his plans, by his words, and by his deeds. He does not

stop praising even in his Passion, because it is particularly

there that God must be praised in carminibus: he perseveres in

praise until he reaches eternity; he continues in praise both

in prosperity and in adversity, until God leads him to perfect

and complete immortality."

The Church has the responsibility and the

commission to continue the praise of Christ here on earth, and she

accomplishes that mission principally through contemplative souls.

Commenting on Psalm 147, Lauda, Jerusalem, Dominum, Bruno writes:

Church, praise the Lord, the Father; praise him as the Lord;

praise, and you will truly be Jerusalem, that is, at peace;

for the Lord this peace is high praise. So, praise the Lord as

your God and your Creator; praise, and you will truly be Zion,

that is, contemplating the things of heaven, and for God this

contemplation is praise in which he takes great pleasure. I

repeat, praise the Lord, your God.

The heart of this Commentary on the Psalms is

Christ, the historical Christ, the mystical Christ, the Church.

This has long been observed by those who have known Bruno's book.

In 1749 Dom Rivet wrote: "Throughout the book, Saint Bruno points

to Jesus Christ and his members, Jesus Christ and his Church."

If the critical works now in progress conclude

that the Commentary on the Psalms is authentic, the outcome would

be very interesting, though not essential, for our full

understanding of Bruno's soul. If these texts date from his time

at Rheims, they indicate that Bruno, the professor of the schools,

was already inclined toward contemplation, if not yet toward the

contemplative life. If they are to be as-signed to the time at

Chartreuse or at Calabria, they add to Bruno's two letters a very

important note about Christ and his Church. They clearly make the

contemplative life part of the Church's very existence and her

activity.

Archbishop Gervais died on July 4, 1067, leaving

a reputation for virtue. Manassès of Gournay succeeded him under

the title of Manassès I. He was consecrated in October of 1068 or

1069. Even though he obtained the See of Rheims through simony and

with the complicity of Philip I, the King of France, Manassès I

administered his diocese in a manner that gave room for hope of a

proper and peaceful administration. But his true character was

soon revealed. Twenty-five years later the chronicler Guibert of

Nogent wrote: "He was a noble man, but he had none of the

moderation that should be characteristic of an honorable man; no,

after his elevation he adopted the ostentations of kings and the

brutality of barbarian princes.... He loved weapons, and he

neglected his clergy. The following statement is reported about

him: `Rheims would be a good See if one did not have to sing Mass

there". He was false and two-faced. To satisfy his appetite for

riches without losing his episcopal See, he skillfully alternated

between wise actions and charitable administration, and the most

flagrant pillage. It was in connection with the succession of

Hérimar, abbot of the renowned abbey of Saint Remi in December

1071, that difficulties came to light. Manassès at first prevented

the monks from giving themselves a new abbot within the time

allowed by the Rule; he was constantly looking for a quarrel with

them, vexing them, and appropriating many of the rich abbey's

possessions. Proof of that comes from the monks, who, during the

year 1072, complained to Pope Alexander II against the Archbishop.

During the first months of 1073, Alexander II died. In April,

Gregory VII succeeded him, and on June 30, 1073, he wrote Manassès

a stern letter:

Beloved brother, if you had regard for your dignity, your

obligations, and the holy prophets, if you had the love that

behooves the Roman Church, you would surely not allow the

prayers and warnings of the Holy See to be repeated so many

times with no effect, especially since it was your errors that

caused them to be issued. How many times did Our venerable

predecessor, how many times did We our-selves beg you not to

allow Us to hear so many complaints from so many brothers who

were driven to despair! We learn from numerous reports that

you are treating this venerable monastery more sternly every

day. What a humiliation it is for Us that the intervention of

the apostolic authority has not yet been able to secure peace

and tranquillity for those who expected your paternal care.

Nevertheless, We wish to attempt once more, with kindness, to

bend your obstinacy, beseeching you, in the name of the holy

apostles and Our own: if you wish to expect Our fraternal love

in the future, repair everything so that We will hear no more

complaints on your account. If you disregard both the

authority of Saint Peter and — insignificant though it may be

— Our friendship, We advise you with regret that you will

provoke the severity and the rigor of the Apostolic See."

Through this letter of the Pope there is a

glimpse of the cynical game Manassès was playing: there were signs

of obedience, promises of submission, and evasion and delay, under

the guise of which, Machiavelli-like, he continued his behavior.

Leaving Rome for Rheims, the messengers from the monks of Saint

Rémi carried this letter addressed to Manassès, along with another

from Gregory VII addressed to Hugh, abbot of Cluny. Hugh was

commissioned by the Pope to deliver the pontifical reprimand to

Manassès, and he was ordered to report to Rome how the affair

proceeded.

Manassès had foreseen the coup and had prepared

for it. Even before the Pope's order reached him, he had placed an

abbot of good reputation over the monks of Saint Rémi. He was

William, then abbot of Saint Arnoul of Metz. In itself the choice

was excellent. But, beginning in the summer of 1073, feeling

himself powerless to restrain the new demands of Manassès, William

asked Gregory VII to accept his resignation. Manassès, he wrote in

his letter, was "a ferocious beast with sharp teeth". The Pope

temporized. At the beginning of 1074 William renewed his petition.

This time he was allowed to take over the rule of his former abbey

again. On March 14, Gregory VII ordered Manassès to proceed with

the regular election of a new abbot. Henry, then abbot of

Humblières, was elected, and he remained in charge until 1095. He

was a powerless witness of the sorrowful events that marked the

remainder of Manassès' administration.

The Archbishop remained almost quiet until 1076.

He even succeeded in regaining the confidence of Gregory VII. He

gave official favor to monastic life in his diocese: when the

monastery of Moiremont, founded by the canons of Rheims (October

21, 1074), was elevated to an abbey, he made a contribution; he

participated in the foundation of the abbey of the canons of Saint

Jean-des-Vignes (1076) ; and he made donations to various

monasteries.

It was during this period that he named Bruno

chancellor of his diocese after the death of Odalric. Should this

choice be seen as a mark of personal esteem, or was it only a

diplomatic gesture? To promote Bruno was to flatter the opinion of

the public and especially of the university and to give a pledge

of goodwill, so great was the esteem that everyone had for Bruno.

Three documents date this brief period during

which Bruno held the office of chancellor. In October 1074,

Odalric was still signing documents as chancellor; but a charter

of the abbey of Saint Basil, dating from 1076, was signed by

Bruno. In April 1078, however, the name of Godfrey replaced

Bruno's on the official documents of the archdiocese. So Bruno's

resignation can be placed in 1077. The fierce conflict that would

ravage the diocese of Rheims for several years began in that year:

on one side were Gregory VII, his legate in France Hugh of Dié,

and several canons of the cathedral; on the other, Archbishop

Manassès I, whose lies were at last uncovered.

At the beginning of this unhappy period, Bruno

was about fifty years old. Though much history is uncertain, some

features of his character stand out, while others remain in

shadow.

Bruno, director of studies for Rheims, is seen

first of all to be a person oriented toward sacred studies, then

as a master and a perfect friend, and finally as a man whose moral

authority is felt by everyone.

Even should the two Commentaries (the one on the

Epistles of Saint Paul and the one on the Psalms) be found by

historical criticism not to be his, Bruno did appear to his

contemporaries as an eminent theologian and a specialist in the

Psalms. The whole of the Eulogies attests that. But his attraction

for the sacred sciences (which is clearly more than mere

curiosity), notably for Saint Paul's thought and the

interpretation of the Psalms, often coincides with his orientation

toward the most profound mysteries of salvation. Because of his

love for the person of Jesus Christ, he concentrated his

attention, the resources of his intelligence, and the effort of

his research upon him who was so close and yet so

incomprehensible. When the Carthusian Fathers of the twentieth

century wanted to express their vocation in a short phrase for an

inscription in the Museum of Corrérie, they borrowed this text

from the Epistle to the Colossians: "Your life is hidden with

Christ in God" (Vita vestra abscondita est cum Christo in Deo).

The simple facts of history are enough: Bruno had decided to

consecrate his life to the study and teaching of the Faith, and

the things of God had captivated his heart and brought

satisfaction to his life.

Not only a renowned scholar but also a master, in

the fully human sense that Saint Augustine gives the word, Bruno

was an excellent teacher. His learning was not only scholarship:

Bruno exercised the spiritual influence that the Eulogies speak of

only because his teaching had been inspired by a profound interest

in man and had deeply touched the religious beliefs and the

essential restlessness of his hearers. He made his pupils into

disciples, often into friends. In the Eulogies regret is often

mingled with warm emotion, beyond literary convention and

catharsis. Bruno aroused more than admiration because he offered

and enkindled friendship. The later years of his life will prove

him better still, because the three in Adam's little garden were

friends that day they determined to turn their life completely

over to God, three friends bound together by their desire for the

things of eternity.

At the end of this long first part of his life

Bruno appeared a man of undisputed moral honor and distinction. It

was by no intrigue that the holy Bishop Gervais and Master

Herimann had agreed to confer the charge of director of studies

for Rheims upon a young man who was not yet thirty years old.

During the twenty years that he held this office, Bruno must have

acquired a reputation for undisputed integrity and authority,

because Manassès I in his anxiety chose him to be chancellor for

the purpose of convincing Gregory VII of his good intentions.

Wasn't Bruno's early resignation from the office of chancellor

another proof of his integrity? Bruno was a just man, in the

biblical sense of the word. Like William, the abbot of Saint

Arnoul, he quickly took the measure of the Archbishop and his

corruption, and it seemed he could have peace only by removing

himself from every risk of compromise and recovering his freedom

to judge and, if necessary, to oppose.

In every society, but especially in a corrupt

one, such devotion for the word of God, such love of noble

friendship, such integrity destine a person to be, in a real

sense, solitary. One who is guileless is always in some way alone.

Bruno was already a "master", not only in the sense that he

mastered his teaching and deeply influenced his pupils but even

more in the sense that he directed events as well as people. He

was above them; he was greater than they; he looked upon them from

his higher vantage point; he saw and judged them. The power of his

personality is demonstrated in the momentous events that are about

to buffet the Church of Rheims.

Bruno confronts Archbishop Manassès

In 1075 the spiritual power of the Pope and the

temporal power of the princes began the long struggle that is

known in history as the struggle of investitures.

Since his election in March of 1074, Gregory VII

had energetically continued the Church reform that his predecessor

had initiated. In 1075 he renewed Alexander's decrees and

strengthened them, condemning the investiture of bishops by

temporal princes. In France the legate commissioned to enforce the

papal decree was an inflexible, merciless man called Hugh of Dié.

His task was thankless, but he under-took it vigorously. It has

been written that he was "the most despised man of the eleventh

century", and he was called "the Church's hatchet man" in France.

At the Pope's command Hugh had to call a series of regional

councils that bishops who were suspected of simony were required

to attend, and those who were found guilty were dismissed from

their office and replaced with trustworthy bishops. The first of

those councils was held in 1075 at Anse, near Lyons. The battle

was begun in the name of the Pope against the dreadful scourge of

simony, and everyone took a stand on the papal reform.

The Council of Clermont was held during the

summer of 1076. The Provost of the Chapter of Rheims, who like his

Archbishop was called Manassès, came of his own accord to Hugh of

Dié and admitted that he had bought his office at the beginning of

1075 after the death of the provost Odalric. He humbly asked to be

forgiven.

It was on the occasion of that meeting, no doubt,

that the Provost Manassès acquainted Hugh of Dié with the

extraordinary situation in which Archbishop Manassès had, through

corruption and violence, involved the diocese of Rheims: the

depreciation of possessions of the Church, arbitrary exactions

from clergy and monks, traffic in offices and benefices,

excommunication threatened against any who opposed him. The higher

authority had to intervene.

Why? Was it because of that complaint and to

circumvent the Archbishop's anger? During the last months of 1076

several important individuals went into voluntary exile from

Rheims, risking the loss of their positions and their possessions.

Ebal count of Roucy-sur-l'Aisne, offered them a place of refuge.

The names of some of these complainants are known: there were the

Provost Manassès, Bruno, Raoul le Verd, and Fulco le Borgne. And

these were surely not the only ones.

The tension between the Archbishop and the exiles

soon reached a critical point. When Gregory VII was informed of

the situation, he decided to intervene, which he did with prudence

and moderation. On March 25, 1077, he directed the Bishop of Paris

to examine the dossier of several who had, apparently, been

unjustly threatened with excommunication by Manassès, still

regarding him as the lawful shepherd of the Church of Rheims. On

May 12 of the same year he again chose him to sit beside Hugh, the

abbot of Cluny, at the head of the Council that was about to take

place at Langres.

All at once the situation was completely

reversed. The plans for Langres were canceled. The Council would

be held at Autun on September 10, 1077. Instead of presiding there

as judge, Bishop Manassès would be summoned and accused. He

refused to appear. But those in exile at Roucy, including the

Provost Manassès and Bruno, came, and they accused their

Archbishop of having obtained the See of Rheims by simony and,

despite the formal prohibition of the Pope, of having consecrated

the Bishop of Senlis, who had received his See through lay

investiture at the hands of the King of France. Bishop Manassès

was suspended from his position by the Fathers of the Council,

"because, though summoned to the Council to give an account of

himself, he did not come" (quid vocatus ad Concilium ut se

purgaret, non venit).

Manassès responded immediately with severe

reprisals against the clerics of Rheims who had gone to Autun. "As

the canons of Rheims were returning after making their accusations

against him at the Council," writes Hugh of Flavigny in his

Chronicle, "the Archbishop ambushed them, sacked their houses,

sold what they had to live on, and confiscated their possessions."

Regardless of the suspension threatened by the

fathers of the Council of Autun, the dispute between Bishop

Manassès and the canons was not resolved. What followed indicates

that the Chapter of Rheims and the legate, Hugh of Dié, must have

felt it urgent to inform Gregory VII. If Marlow's History of the

Church of Rheims can be believed, the Chapter would have sent

Bruno himself (and perhaps Manassès) to Rome so they could tell

the Pope personally about the excesses of the Archbishop. Be that

as it may, an account by Hugh of Dié relates (some authors say it

was through two letters) the part played by the Provost and by

Bruno in the resistance to the Bishop. The delegate to Gregory VII

wrote:

To Your Holiness we recommend our friend in Christ, Manassès,

who resigned his office of provost of the Church of Rheims

during the Council of Clermont. Though he had obtained his

position unlawfully, he is a sincere defender of the Catholic

Faith. We also recommend Bruno, a teacher with integrity in

the Church of Rheims. Both of them deserve to be confirmed for

divine service by your authority, because they have been

judged worthy of suffering persecution for the name of Jesus.

Please use them as your counsellors and cooperators for the

cause of God in France.

This is an authentic and important testimonial to

the high regard that the legate and everyone else at Rheims

(except the simoniac Archbishop) had for Bruno. For Hugh of Dié to

bestow so formal an encomium upon someone, saying, "His life is

irreproachable" or calling him "master of all integrity in the

Church of Rheims", there must have been no shadow on his conduct.

Bruno's faith, virtue, and honor were beyond suspicion. He stood

above this troubled period for the Church of Rheims like one

without guile, who had not compromised at all.

As a matter of fact, Gregory VII did not confirm

the judgment of the Council of Autun immediately. He soon wrote

that the Roman Church was accustomed to act with "a measure of

discretion rather than the rigor of law". The Pope recognized his

legate's tendency to be severe. Had he not perhaps judged too

quickly, extinguishing the wick instead of encouraging it to flame

again? He decided to examine the case of Manassès himself, as well

as the six other bishops who had been condemned by Hugh of Dié. To

do that he called them to Rome and invited them to explain. Count

Ebal of Roucy, and Ponce, one of the canons of Rheims, came with

them to tell Gregory VII just what had happened at Rheims. At Rome

the discussion was difficult. The principal argument that Manassès

dared to propose in his own defense was that to condemn him would

be to risk creating a schism within the kingdom! Finally Manassès

flared up at his accusers. Upon an oath "on the body of Saint

Peter", he obtained pardon from Gregory VII. On March 9, 1078,

Gregory VII addressed the following letter to the legate:

Because it is the custom of the Roman Church, at the head of

which God has placed Us in spite Our unworthiness, to tolerate

certain actions and to let some pass in silence, We have

decided to use moderation rather than demand the strictness of

the law, and We have very carefully reexamined the cases of

the bishops of France who were suspended or condemned by our

legate, Hugh of Dié. Although Manassès, the Archbishop of

Rheims, has been accused on several counts, and although he

refused to appear at the Council to which Hugh of Dié had

summoned him, it seems to Us that the sentence against him was

not in conformity with the compassion and gentleness customary

in the Roman Church. For this reason We restored him to the

duties of his office after he took this oath on the body of

Saint Peter: "I, Manassès, declare that it was not out of

pride that I did not appear at the Council of Autun, to which

the Bishop of Dié had summoned me. If I were called by a

messenger or a letter from the Holy See, I would not use any

pretext or deceit to escape. I would come and loyally submit

to the decision and judgment of the Church. If it pleases Pope

Gregory or his successor that I give an account before his

legate, I shall obey with the same humility. I shall not use

the treasures, the resources, or the possessions of the Church

of Rheims, which are entrusted to my care, except for the

honor of that church, and I shall not dispose of them in any

way that I could be accused of failing injustice." So,

Manassès was enfolded in a judgment of leniency and mercy,

which closed the inquiry and the case of the bishops.

This gentleness was not what the legate, Hugh of

Dié, wanted from the Pope. Would it not destroy his authority? He

wrote to the Pope with some bitterness to let him know of his

disagreement:

May Your Holiness grant that no longer will anyone insult us

and dishonor us. Those that we suspended, deposed, or even

condemned, who were guilty of simony or anything else, freely

have recourse to Rome, and there, where they should meet with

strict justice, they find the mercy they desire. Those who

previously did not dare to sin even in trifling things, begin

to indulge in more profitable dealings, tyrannizing over the

churches they are in charge of. Believe me, most holy Father,

Your Holiness' useless servant.

No doubt the legate's complaint went beyond the

case of the Archbishop of Rheims, but it did include him.

Returning to his diocese, Manassès played the penitent to extend

and consolidate his victory. He attempted to be reconciled with

the Provost, with Bruno, and with the other canons who had taken

refuge with Count Ebal and, in good time and in proper form, to

obtain a papal condemnation against the Count. To free his hands

for further intrigues, he even asked the Pope to make him subject

no longer to the jurisdiction of Hugh of Dié any longer but only

to the authority of the Pope or legates who come from Rome. Then

with shameless wheedling he wrote at length to Gregory VII. He

repeatedly proclaimed his fidelity and homage; he accused, he

argued, he invoked the privileges granted to his predecessors; and

finally he came to the exiles and their protector:

As regards Count Ebal, who attempted to accuse me in your

presence, appealed to you, and affirmed his fidelity to you

with hypocritical words, you were able to recognize which side

was showing you sincerity and fidelity: mine, where I am

prepared to obey God and you in everything, or the side of the

Count of Ebal, who in your presence attacked the Church of

Saint Peter and in our presence persecutes the Church of

Rheims through the Provost Manassès and his partisans, who

gathered at his chateau. This Manassès has received the

assurance of forgiveness, which you ordered us to grant him if

he returned to the Church, his mother; but, paralyzed in the

knowledge of his sins, he chooses neither to return to us nor

to yield to the peace of the Church. On the contrary, he does

not cease, nor do his followers, to revile my church and

myself by derogatory language, since he may not inflict

physical blows. Further, without speaking of Count Ebal, who,

I trust, will not escape your just and apostolic sentence, I

urgently beseech your Holiness to order Manassès to return

home and attack his church no longer; or better, frighten him

and his supporters and his cooperators with a stern, apostolic

sentence. Be so kind as to write to those who have received

them and tell them to give them asylum against the rights of

the Church no longer under pain of similar sentence.

It was a deceitful tactic. The phrase "without

speaking of Count Ebal" insinuates that the sentence of

condemnation has passed from himself. Putting that first, in the

place of Manassès, who was not without reproach; saying nothing

about Bruno, whom, the Archbishop well knew, the Pope considered a

virtuous and honorable man — all that was clever, too clever. The

Pope did not permit himself to be taken by surprise again. He

outmaneuvered every trap. On August 22, 1078, he sent a reply to

Manassès' letter. In his excellent reply the Pontiff again

attempted to avoid an open break with the Archbishop and to design

an honorable withdrawal for him if he should agree to be sincere

and trustworthy. He reassured him of his loyalty and guaranteed

him his rights as bishop and metropolitan. But Manassès will give

up every exemption: he will not place himself above the law, and

he will recognize the authority of the papal legates even if they

do not come from Rome, specifically the authority of Hugh of Dié

with whom, in an effort to avoid any excessive strictness, he

associated the Abbot of Cluny, who was known for his moderate

judgments. The Provost Manassès too will be subjected to a just

and precise investigation by the two legates: "Regarding the

Provost Manassès who, you say, never ceases to annoy you by his

words since he cannot do it by his acts, and against whom you have

made any other accusations you please, We are sending you Our

instructions for Our dear brothers the Bishop of Dié and the Abbot

of Cluny, so that they will try to conduct a diligent inquiry into

these affairs, to examine them carefully, and to judge them in all

truth and justice in conformity with canon law."

For the Pope, these were not idle words. On that

very day he sent his instructions to Hugh of Dié and Hugh of

Cluny. They were measured words. Gregory VII's wisdom and his

perfect knowledge of each of his collaborators shine through them.

He directed the legates to "strive to reconcile the provost

Manassès, whom the Archbishop complained of, the one who had fled

to Count Ebal and, aided by him, has not ceased to disturb the

Archbishop and his church. He should desist from disturbing the

church and persecuting the Bishop. If he is stubborn and does not

wish to obey, do with him what seems right to you." To the Provost

these instructions seemed to be harsh, and they were. They reveal

the seriousness of the conflict that set the Archbishop and the

exiled canons against each another. But the Pope added a little

clause that showed that he was well informed about the matter and

wondered whether the Provost's resistance might not be justified:

"Unless you find out that he has just cause for what he is doing".

Everything should be done in accordance with law and justice. In

charity, the legates will place all their energy at the service of

law and justice. In this painful conflict charity must prevail.

Regarding the other demands of the Archbishop, assist him as

is proper, if he obeys you, and with the authority of the

apostles defend the church which has been placed in his care.

As regards himself, We have been informed by the letters you

have written to Us that he is seeking delays and deceit. We

have told him by letter exactly what We are writing to you

today. My dear brothers, act with strength and wisdom, and do

everything with charity. May the oppressed find you prudent

defenders, and may their oppressors see your love of justice.

May the all-powerful God pour his Spirit into your hearts!"

We do not know for sure what happened at the end

of 1078 and during the first months of 1079. The fact is that, at

midsummer of that year, the legate Hugh of Dié, in agreement with

the Abbot of Cluny, judged it expedient to convoke a Council at

Trent and summon Archbishop Manassès to it. He came, along with an

escort of numerous supporters, intending that their show of

numbers would surely bring pressure upon the Council. Did he do

this to prevent the Council from deliberating or making free

judgments? At the last moment the legate canceled the Council.

Gregory VII decided to intervene and subject the

Arch-bishop's conduct to a new scrutiny. He wrote this order to

Hugh of Dié:

Since you were unable to convoke a Council in the place that

was planned, We judge it advisable now that you find a

suitable location to hold a synod and carefully examine the

case of the Archbishop of Rheims. If trustworthy accusers and

witnesses are found who can prove canonically the charges

against him, We desire that you carry out without delay the

sentence that justice will determine. On the other hand, if

such witnesses cannot be found, now that this Archbishop's

reputation for scandal has spread not only throughout France

but also almost all of Italy, let him bring, if he can, six

bishops of unblemished character. If they find him innocent,

he will be exonerated and permitted to live at peace in his

church with his prerogatives.

To put this case in perspective, the conflict in

which the provost Manassès, Bruno, and the canons of Rheims were

involved was not an internal dispute in a single diocese, a mere

"sacristy argument". The importance of Rheims in France and the

pompous excesses of the Archbishop took the affair beyond the

diocese of Rheims. The scandal touched all of France and most of

Italy. For that reason Gregory VII imposed this unusual procedure

upon his legates. If the wit-nesses for the prosecution failed to

make the accusation clear and undeniable, the Archbishop would not

for that reason be found innocent; it would be for him to prove

positively that his conduct and his intentions were honorable. Six

bishops "of unblemished character" must personally attest to the

morality of his conduct and his fitness to remain at the head of

the Church of Rheims. This policy was a strong challenge to

Manassès and his intrigues.

Following the Pope's orders, Hugh of Dié convoked

a new council. Lyons was chosen to be the place for it. The date

was set for the first days of February 1080. Manassès again

appealed to the Pope over the head of the legate, invoking an

ancient privilege of the Church of Rheims according to which the

Archbishop was responsible only to the Holy See. Gregory VII

responded on January 5, 1080, refusing him the right to challenge

the jurisdiction of his legate, Hugh of Dié, who would be assisted

by the Bishop of Albano, Cardinal Peter Ignée, and Hugh of Cluny.

Gregory wrote:

We are astonished that so wise a man as you finds so many

excuses to remain isolated and hold on to your church in the

face of such disgraceful accusations and allow public opinion

to judge you, when you should be interested in removing

suspicions like these and freeing your church from them. If

you do not go to the Council of Lyons, if you do not obey the

Roman Church, which has put up with you for a long time, We

shall in no way change the decision of the Bishop of Dié;